Month: July 2013

-

/

6448 SEEN/

Bid rules at Broward Aviation are different; company cries foul

By William Hladky

BrowardBulldog.org

The rules are different at the Broward County Aviation Department. Although the Broward County Commission in 2011 approved a major overhaul of the county’s procurement code, the rule changes only partially affected the Aviation Department. -

/

5098 SEEN/

The other Washington could hold the key to Medicare’s cost crisis

By Joe Eaton

Center for Public Integrity

A recent federal assessment of Medicare’s fiscal health contained a shred of good news — the public health insurance program for the elderly is burning through cash at a slightly slower rate than expected. Yet declining health care costs haven’t bought much time. -

Amid intrigue and suspicion, Broward sheriff to award $145 million jail healthcare contract

By Dan Christensen

BrowardBulldog.org

Broward Sheriff Scott Israel is expected soon to award a contact worth as much as $145 million over the next five years for the delivery of healthcare services to the county’s approximately 5,000 jail inmates. The road to a deal has been full of turns, with intrigue and suspicion around every curve. -

/

5108 SEEN/

ObamaCare oversight: Budget squeeze forces HHS watchdog to trim investigative targets

By Fred Schulte

Center for Public Integrity

Facing major budget and staff cuts, federal officials are scaling back several high-profile health care fraud and abuse investigations, including an audit of the state insurance exchanges that are set to open later this year as a key provision of the Affordable Care Act. -

/

4692 SEEN/

Syria’s Jihadi migration emerges as top terror threat in Europe, beyond

By Sebastian Rotella

ProPublica

Rachid Wahbi came to Syria from a Spanish slum, rushing toward death. And he didn’t plan to die alone. -

/

5305 SEEN/

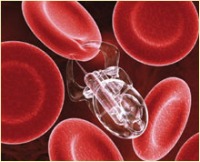

Nanotechnology: Harmful or benign?

By Sheila Kaplan

Investigative Reporting Workshop

Nanotechnology is a booming industry, with growth an any industry would envy. But reports from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), GAO, academic researchers and manufacturers reveal the downside of such rapid development: Nobody really knows if these wonder products are safe.

Support Florida Bulldog

If you believe in the value of watchdog journalism please make your tax-deductible contribution today.

We are a 501(c)(3) organization. All donations are tax deductible.

Join Our Email List

Florida Bulldog delivers fact-based watchdog reporting as a public service that’s essential to a free and democratic society. We are nonprofit, independent, nonpartisan, experienced. No fake news here.